The first time I entered the Pantheon, I didn’t just walk—I paused. The Roman portico invites familiarity. But once you pass those ancient bronze doors, you’re not in a building anymore. You’re inside a concept. A hemisphere unfolds above, a vast unreinforced concrete dome that seems to float, balanced impossibly on a drum of stone and light. The oculus opens not only to the sky, but to time itself.

It is this moment—where silence meets geometry, where awe becomes inquiry—that frames both this article and the book it introduces: The Pantheon Dome – Ancient Ingenuity, Modern Lessons. This is not simply a celebration of antiquity, but a study of what Rome’s most enduring structure still teaches us.

Rome Ascendant: Architecture as Empire

Commissioned under Emperor Hadrian in the early 2nd century CE, the Pantheon was a reinvention, not a restoration. Agrippa’s original temple had burned. Rather than rebuild it in the same form, Hadrian recast it as a sphere within a cylinder—a temple not just to all gods, but to the cosmos itself.

Hadrian’s Rome was about consolidation, not conquest. His building program focused on permanence, proportion, and symbolism. The Pantheon, positioned in the Campus Martius, was his architectural manifesto. A square portico rooted in tradition; a circular dome opening into the infinite.

The Dome as Engineering Masterpiece

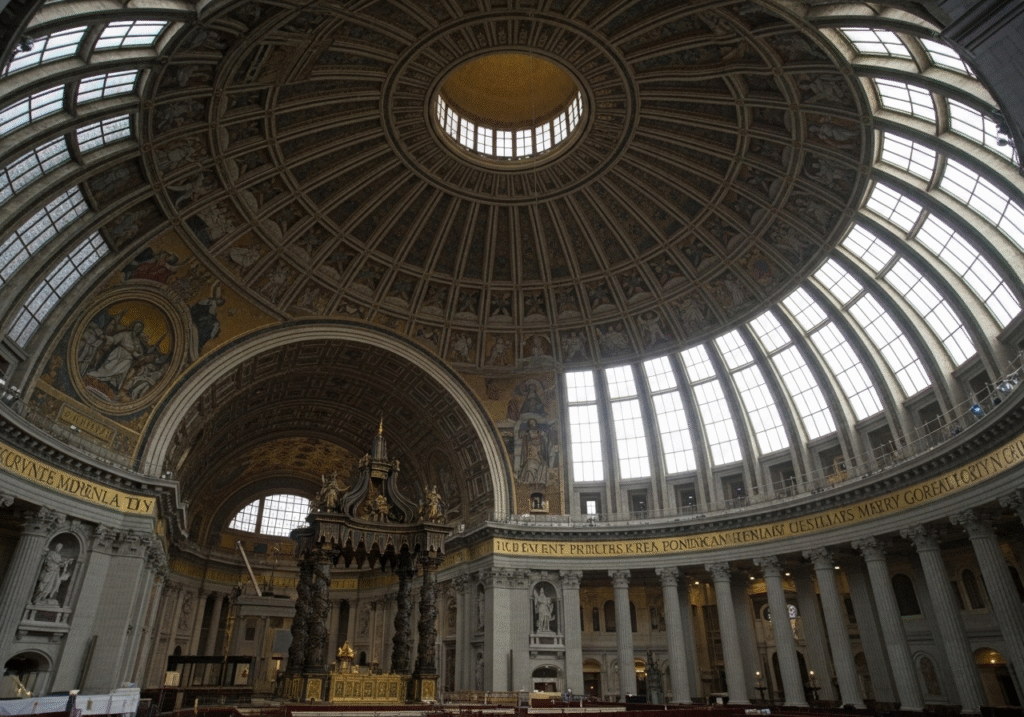

At 43.3 meters in diameter, the Pantheon’s dome remains the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome nearly 2,000 years after its completion. But size alone is not its triumph. The dome is a lesson in gravitational management:

Coffers lighten the load structurally and visually

Gradated concrete uses denser aggregates at the base, lighter pumice near the oculus

Hidden chambers in the drum absorb lateral thrust

Every element reflects an empirical intelligence that modern engineers still marvel at. The builders didn’t use steel. They used insight.

Sacred Geometry and Cosmic Order

Geometry was not ornament—it was theology. The Pantheon’s form is derived from two primal shapes: the square (earth) and the circle (heaven). These were not just Platonic ideals, but architectural decisions. The building is a sphere inscribed in a cylinder. The oculus, nearly 9 meters wide, is its zenith.

Light enters through this eye of the heavens, transforming the interior throughout the day. At specific times—especially April 21st, the traditional founding date of Rome—the sunbeam aligns with the entrance. Architecture becomes calendar. Ceremony becomes cosmos.

Sacred Geometry and Cosmic Order

Geometry was not ornament—it was theology. The Pantheon’s form is derived from two primal shapes: the square (earth) and the circle (heaven). These were not just Platonic ideals, but architectural decisions. The building is a sphere inscribed in a cylinder. The oculus, nearly 9 meters wide, is its zenith.

Light enters through this eye of the heavens, transforming the interior throughout the day. At specific times—especially April 21st, the traditional founding date of Rome—the sunbeam aligns with the entrance. Architecture becomes calendar. Ceremony becomes cosmos.

Global Echoes and Modern Lessons

The Pantheon has influenced every generation of builders since the Renaissance. Brunelleschi studied it before designing Florence’s dome. Michelangelo called it “angelic, not human” before shaping St. Peter’s. Jefferson, Wren, and countless others echoed its form in civic monuments across the globe.

But beyond form, the Pantheon offers lessons for our era:

Build for longevity — not obsolescence

Let light animate space — not just artificial systems

Unite engineering and meaning — not one without the other

In an age of disposability, the Pantheon urges us to think in centuries, not cycles.

Architecture as Dialogue

Ultimately, the Pantheon is more than a structure. It is a dialogue—between earth and sky, matter and metaphor, history and possibility. To stand within it is to be reminded that architecture is not simply built—it is experienced.

Through The Pantheon Dome – Ancient Ingenuity, Modern Lessons, we explore not only how the building was made, but why it still matters. It is an invitation to architects, engineers, historians, and dreamers to step into the center of a perfect circle—and listen.