The 2021 International Residential Code (IRC) marks a turning point in the treatment of alternative construction methods. Historically, the IRC has been anchored in prescriptive solutions, reflecting mainstream building materials and techniques. But the 2021 edition pushes the boundaries, acknowledging a wider array of innovative methods—ranging from straw-bale and cob to 3D-printed homes and shipping container structures—by formalizing their legitimacy through new appendices and revised equivalency procedures.

Alternative construction methods are no longer marginal practices relegated to the periphery of code compliance. With Appendices AR (light straw-clay), AS (straw-bale), AU (cob), and AW (3D printing), and reinforced by Section R104.11, the 2021 IRC codifies pathways for builders, designers, and jurisdictions to explore unconventional approaches without compromising safety, durability, or performance.

Understanding IRC Section R104.11: The Equivalency Framework

Section R104.11 serves as the cornerstone for integrating alternative materials and methods into mainstream construction. It grants the building official authority to approve any material, design, or construction method not explicitly prescribed by the code, provided it achieves equivalency in quality, strength, effectiveness, fire resistance, durability, and safety. The provision does not offer a shortcut—it imposes a rigorous burden of proof on the applicant, who must substantiate claims through technical data, testing, and authoritative documentation.

The code also details the procedures for evaluating these alternatives. Section R104.11.1 empowers building officials to require independent testing when there is insufficient evidence of compliance. These tests must align with recognized standards or, in their absence, be approved by the official. Reports are retained as public records, reinforcing transparency and accountability.

This framework has created a robust, performance-based path for alternative construction, allowing innovation to occur within the legal boundaries of code compliance. However, it also places a premium on collaboration between applicants and code officials, as well as on meticulous preparation and documentation.

Codified Alternatives: Appendices That Changed the Landscape

The 2021 IRC makes notable strides by formalizing three major alternative methods via new appendices:

Appendix AS: Straw-Bale Construction

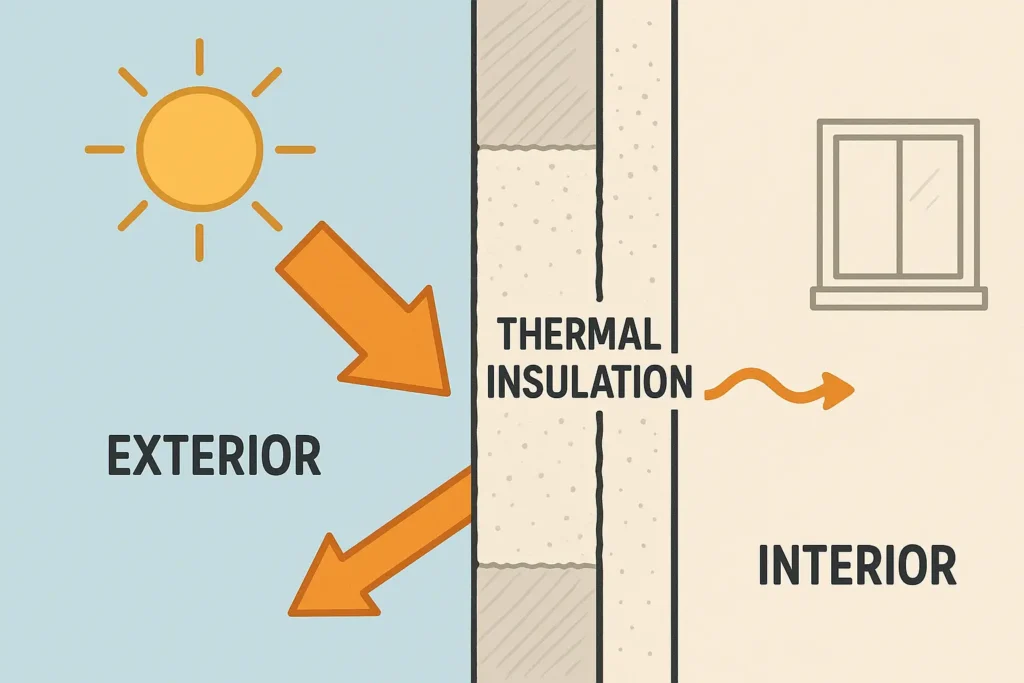

Straw-bale construction, although rooted in 19th-century building practices, is now recognized in Appendix AS. It outlines prescriptive methods for both load-bearing and infill systems, defining plaster specifications, compression requirements, and wall assembly details. The R-values achievable through straw-bale assemblies can surpass conventional framing when properly detailed, and the plaster skins are structurally active in resisting wind and seismic loads.

Appendix AS also addresses moisture management, fire resistance, and even includes provisions for a “truth window,” offering a rare intersection of performance and storytelling in code compliance.

Appendix AR: Light Straw-Clay Construction

Light straw-clay, a method using straw mixed with clay and tamped into wall cavities, is codified for non-load-bearing applications. Like straw-bale, its acceptance within the code formalizes its legitimacy, especially among builders focused on natural materials and passive energy performance. Appendix AR includes braced wall panel criteria and details for plastered finishes.

Appendix AU: Cob Construction

Cob construction—essentially clay, sand, and straw mixed and applied in monolithic earthen walls—is now provided for both bearing and nonbearing walls. Appendix AU offers 16 pages of provisions covering wall dimensions, plaster skins, reinforcement, and seismic considerations. The codification of cob demonstrates how ancient methods are being revived with modern engineering oversight.

Appendix AW: 3D-Printed Construction

With over a page of guidance, Appendix AW legitimizes additive manufacturing techniques. It provides jurisdictional pathways for evaluating load-bearing and fire-resistance properties in printed structures. Early projects have proven viable, particularly for affordable housing and disaster recovery, although broader adoption depends on ongoing collaboration between code officials and engineers.

Appendix AW: 3D-Printed Construction

With over a page of guidance, Appendix AW legitimizes additive manufacturing techniques. It provides jurisdictional pathways for evaluating load-bearing and fire-resistance properties in printed structures. Early projects have proven viable, particularly for affordable housing and disaster recovery, although broader adoption depends on ongoing collaboration between code officials and engineers.

The Realities of Approval: From Testing to Equivalency

In practice, achieving approval under R104.11 requires significant documentation. This includes:

Detailed construction drawings

Engineering calculations

Material test reports (e.g., ASTM standards)

Fire resistance and energy performance data

Research reports from authoritative agencies

Failure to provide satisfactory evidence is a valid basis for denial. The code ensures due process: if an alternative is rejected, the official must provide a written explanation. This procedural transparency is critical, particularly in jurisdictions where unfamiliarity with natural or emerging methods might otherwise stifle innovation.

In one real-world example from the Midwest, a straw-bale home was approved after the design team submitted compression testing data, R-value calculations, and plaster shear strength tests from a recognized laboratory. The home not only passed inspection but also exceeded energy benchmarks.

Adoption Challenges and Jurisdictional Variability

Despite the IRC’s progressive posture, adoption of these appendices remains optional. Jurisdictions must choose to include them during the local code adoption process. As a result, builders face a patchwork of regulatory environments where an alternative method might be code-compliant in one county but deemed unrecognizable in the next.

Cost is another hurdle. While some alternative materials are inexpensive, the documentation, testing, and engineering oversight required to satisfy equivalency can offset those savings. Moreover, inspectors unfamiliar with alternative methods may default to conservative judgments unless clear, reproducible standards are presented.

Bridging Tradition and Innovation: The Role of Design Professionals

Architects and engineers play a pivotal role in navigating the space between innovation and regulation. Their involvement often determines whether a novel method is seen as risky or as a forward-thinking solution grounded in engineering rigor. In projects using cob or light straw-clay, for example, the integration of code-calibrated calculations and clear wall detailing has been the key to building official approval.

Design professionals also serve as educators—preparing documentation, referencing past approvals, and advocating for local adoption of appendices. Their expertise bridges the cultural gap between traditional codes and alternative material performance.

The Path Forward: Innovation Through Compliance

The 2021 IRC’s treatment of alternative construction methods reflects a broader shift in residential design: innovation must occur within a framework of verifiable safety and performance. The code does not aim to stifle new ideas; rather, it demands that they be proven.

By formalizing both the process (via R104.11) and the methods (through dedicated appendices), the IRC offers a dual path forward—flexibility without compromise. For those willing to meet the rigorous demands of equivalency, a world of material and design innovation is now available under the umbrella of code compliance.

As jurisdictions continue to adapt, and as practitioners build a stronger body of test data and case studies, the presence of alternative construction in the residential mainstream will only grow. The IRC 2021 is not just a regulatory document—it is a roadmap for responsible innovation.

Dr. Riley Carter

Architect | Educator | Passive House Advocate