As an architect who has spent over two decades examining how building codes and design shape our communities, I’m often asked about the connection between a single building and the city as a whole. The answer lies in architecture urbanism—the dynamic interplay between the design of individual structures and the planning of the entire urban fabric. It’s the art and science of creating not just beautiful buildings, but livable, equitable, and resilient cities.

To truly understand our cities today, we need to look at where urbanism comes from and, more importantly, where it is going.

What is the True Relationship Between Architecture and Urbanism?

Many see architecture as the creation of standalone objects—a skyscraper, a museum, a home. But from an architect’s perspective, no building exists in a vacuum. It speaks to the street, influences the flow of people, and contributes to the character of a neighborhood. Urbanism is the broader context; it’s the design of the systems—transportation, public spaces, zoning—that connect these buildings.

Effective architecture urbanism happens when these two scales are in perfect dialogue. A well-designed public plaza is only as good as the buildings that frame it, and an innovative, sustainable building has a far greater impact when it’s part of a walkable, mixed-use neighborhood. My work often focuses on how a single home’s design, through its materials and orientation, can contribute to a more energy-efficient and neighborly streetscape. This is the intersection where a single blueprint can influence an entire community.

A Brief History: Where Urbanism Comes From

To design the cities of tomorrow, we must learn from the visions of the past. The history of urbanism is a fascinating story of humanity’s attempts to bring order, efficiency, and meaning to our collective lives.

The Grid and the Garden City: Early Visions of Order

Early city planning was often about control and efficiency. The rigid grid plan, used by the Romans and later adopted in many American cities, was brilliant for navigation and subdivision of land. In reaction to the industrial city’s pollution and overcrowding, visionaries like Ebenezer Howard proposed the “Garden City”—a model that sought to combine the best of town and country with greenbelts and distinct zones for living, working, and recreation.

Modernism’s Grand Plans and Their Unintended Consequences

The 20th century saw the rise of Modernist architects like Le Corbusier, who envisioned utopian cities of towering high-rises set in park-like landscapes, connected by highways. While the intention was to create light, air, and efficiency, these “towers in the park” projects often dismantled the fine-grained, walkable urban fabric they replaced. They separated uses (living, working, shopping) and prioritized the automobile, leading to social isolation and lifeless public spaces.

The Rise of New Urbanism and Community-Centric Design

By the late 20th century, a powerful counter-movement emerged, championed by thinkers like Jane Jacobs. She argued for the value of dense, mixed-use, and pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods. This philosophy, which evolved into New Urbanism, is something I remember studying with fascination. Her ideas on the importance of “eyes on the street” and short, walkable blocks were revolutionary then, but today they form the bedrock of sustainable city planning and architecture.

Today’s Defining Trends: An Architect’s Analysis

We are at a pivotal moment. Pressing challenges like climate change, social inequality, and rapid technological shifts are reshaping the priorities of architecture urbanism. Here are the key trends I see defining our cities right now.

The Sustainability Imperative: From Passive House to Mass Timber

Sustainability is no longer a niche interest; it’s the central organizing principle of modern urban design. This goes far beyond adding a few solar panels.

Mass Timber Construction: Projects like the proposed new Vancouver Art Gallery showcase the move toward materials like mass timber. It’s a renewable resource that sequesters carbon, making it a powerful tool in building greener cities.

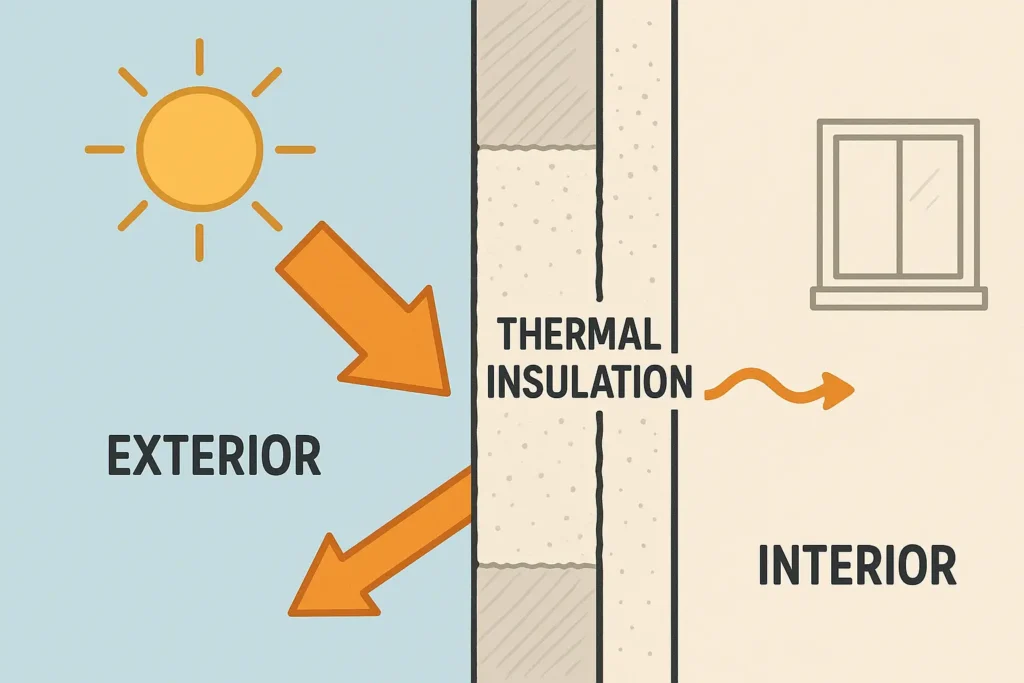

Passive House Standards: As an expert in Passive House design, I’ve seen it evolve from a fringe concept to a mainstream goal. This rigorous standard for energy efficiency drastically reduces a building’s heating and cooling needs. When applied at a neighborhood scale, it can fundamentally lower a city’s carbon footprint.

Green Infrastructure: Cities are integrating nature back into the urban fabric with green roofs, permeable pavements, and protected green networks, which help manage stormwater, reduce the urban heat island effect, and improve well-being.

Technology and the Smart City: More Than Just Gadgets

The “smart city” concept is maturing from a tech-focused buzzword into a human-centric strategy. It’s not just about sensors and data, but about using technology to improve services, enhance communication, and increase efficiency. This includes everything from intelligent traffic management systems that reduce congestion to apps that help citizens engage with local government. The key is ensuring this technology serves people and promotes equity, rather than creating a new digital divide.

Social Equity and Inclusive Design: Building for Everyone

A great city must work for all its residents. There is a growing recognition that urban planning has historically created and reinforced inequalities. Today, the focus is on inclusive design. The collaboration with Indigenous architects on the Vancouver Art Gallery is a prime example, ensuring that the building reflects the region’s history and cultural identity. This trend also involves designing accessible public spaces, ensuring housing affordability through inclusionary zoning, and creating cities where people from all walks of life feel they belong.

Post-Pandemic Shifts: The Demand for Flexible, Green Public Spaces

The pandemic was a stress test for our cities. It taught us the critical value of our immediate surroundings—our homes, our neighborhoods, and our local parks. From my perspective as an architect designing homes, the demand has skyrocketed for features that enhance livability, such as functional balconies, access to shared green spaces, and adaptable rooms that can serve as a home office. At the urban scale, cities are reclaiming streets for pedestrians and cyclists, creating “streeteries,” and investing in high-quality public spaces that serve as our collective backyards.

The Future of Architecture Urbanism: Where Are We Going?

The trends of today point toward an exciting and challenging future for our cities. Here are the concepts that are moving from theory to reality.

The 15-Minute City: Hyper-Local Living

The concept of the “15-minute city,” where all essential needs—work, shopping, education, healthcare, and recreation—are accessible within a 15-minute walk or bike ride, is gaining global traction. This is a radical shift away from car-dependent, zoned suburbs and toward creating self-sufficient, vibrant neighborhoods. It’s the logical evolution of Jane Jacobs’ vision, supercharged by a new focus on sustainability and quality of life.

Resilience and Adaptation: Designing for Climate Change

Our future cities must be designed to withstand and adapt to the realities of climate change. This means building in coastal areas that can handle sea-level rise, designing “sponge cities” that absorb extreme rainfall, and using materials that can withstand higher temperatures. Urban resilience is no longer an option; it’s an essential survival strategy.

The Symbiotic City: Blurring Lines Between Nature and the Built Environment

Perhaps the most inspiring vision for the future is the idea of a city that functions as an ecosystem. The theme of the 5th Seoul Biennale, “Land Architecture, Land Urbanism,” points directly to this. It imagines cities where buildings generate their own energy, recycle their own water, and are interwoven with productive landscapes and thriving biodiversity. This is the ultimate goal: to move from cities that consume resources to cities that regenerate them.

Actionable Insights: 3 Tips for a Better Urban Future

As both an architect and a resident, I believe the best cities are shaped not just by professionals but by the people who inhabit them. Here are three things you can do to contribute to a better urban future in your community.

Advocate for Mixed-Use Zoning: One of the biggest barriers to creating walkable, vibrant neighborhoods is outdated zoning that strictly separates residential, commercial, and industrial areas. Support local policies that allow for a mix of uses, enabling small businesses to thrive and reducing our reliance on cars.

Champion Green Infrastructure: Demand more from your public spaces. Advocate for more parks, street trees, community gardens, and greenways. This not only makes your city more beautiful and pleasant but also more resilient and ecologically healthy.

Get Involved in Local Planning: Your voice matters. Attend public meetings about new developments, join your neighborhood association, and communicate with your local representatives. The future of your city is being decided now, and informed, passionate citizens are the most powerful force for positive change.

Building Tomorrow’s Cities, Together

Architecture urbanism is more than an academic field; it is the ongoing, collective project of building our future. From the historical grid to the future symbiotic city, the way we design our built environment reflects our values, our challenges, and our aspirations. By embracing sustainability, equity, and community-centric design, we can create cities that are not only smarter and safer but also more joyful and inspiring for generations to come.