A Clear Explanation for Homeowners, Builders, and Anyone Navigating U.S. Building Codes

Whenever people first explore building regulations in the United States, two acronyms appear almost immediately: IRC and IBC. And almost always, those two terms get mixed up. In my work, I’ve seen homeowners, designers, and even new builders call them “the residential code” and “the commercial code,” which sounds logical — but is actually inaccurate.

The truth is much simpler, and at the same time much more nuanced. Understanding the difference between the International Residential Code (IRC) and the International Building Code (IBC) can save thousands of dollars in redesigns, avoid delays during permitting, and set realistic expectations for what a project will require. And as someone who has spent years helping clients navigate the dividing line between these two codes, I know exactly where the confusion begins.

Why These Two Codes Even Exist

Both the IRC and the IBC come from the International Code Council (ICC). ICC publishes model codes that states and cities adapt into local law. The reason there are two separate codes is simple:

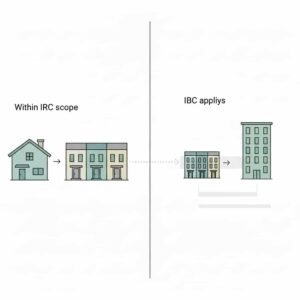

not all buildings are the same, and the construction of a small two-story home is nothing like the construction of a five-story apartment building or mixed-use structure.

So instead of forcing all buildings to follow the same set of complex rules, ICC created a streamlined, prescriptive code (the IRC) for the most common type of home in America — and a comprehensive, technical code (the IBC) for everything else.

This is where many people get lost: if both are “building codes,” which one applies to which building?

The IRC: The Code for Homes That Fit a Very Specific Definition

The International Residential Code applies to a group of buildings that are surprisingly narrow in scope. In fact, most of the confusion I see comes from how limited the IRC actually is.

Under the code, a project qualifies for the IRC only if it is:

a detached one- or two-family dwelling, or

a townhouse

and does not exceed three stories above grade plane

and has its own independent means of egress

including its accessory structures (garages, sheds, etc.)

If a building meets that definition, it belongs to the IRC. Not because it’s “residential,” but because it fits the specific category the IRC was written for.

What makes the IRC popular with homeowners and small builders is its nature: it is prescriptive, meaning it offers clear, direct instructions. It’s easier to understand, easier to design under, and generally less expensive to comply with.

I often explain to clients that the IRC is like a detailed recipe: follow the steps, and you’re compliant. That clarity is one reason it’s widely used for smaller homes.

The IBC: The Code for Everything Outside the IRC

Then comes the International Building Code, which covers every other building type — residential, commercial, institutional, industrial, and more. A common misconception is that the IBC is “the commercial code,” but in practice it applies to a wide variety of residential buildings too.

If a project does not meet the IRC’s narrow definition, it automatically falls under the IBC.

Three stories turn into four? IBC.

Two dwelling units turn into three? IBC.

Townhouses built above the height limit? IBC.

Mixed-use building with a store below and apartments above? IBC.

The IBC is designed for complexity. It involves engineering, fire protection strategies, egress systems, occupancy classifications, and provisions for every building type imaginable. The IBC is thicker, more technical, and more comprehensive because it has to be.

From an architectural standpoint, once a project crosses into IBC territory, the design team must consider additional structural requirements, fire ratings, emergency access, and detailed documentation. These are all factors that affect construction cost and timeline — and understanding that early helps set realistic expectations.

Where People Get Confused — And Why It Matters

When someone searches the internet for “the international building code,” the results often include both IRC and IBC references. It’s extremely common for people to think they’re interchangeable, or that one is simply a smaller version of the other.

In practice, the confusion usually comes from three things:

1. The names sound nearly identical.

Both contain “International,” “Code,” and “Building,” which doesn’t help newcomers understand their roles.

2. People assume “residential = IRC,” which is not always true.

I have worked with clients designing three-family homes who were shocked to learn they fell under the IBC.

And townhouse developers frequently discover that adding a fourth story suddenly triggers a complete code shift.

3. Most homeowners encounter building codes for the first time during a project.

By then, misunderstandings can cause delays or costly redesigns — something I try to prevent by explaining IRC vs IBC clearly at the start.

This is why I emphasize the distinction early with clients, especially those building custom homes or planning additions that might exceed the IRC’s prescriptive limits. A simple assumption about “residential code” can snowball into major issues later.

Real-World Examples of Which Code Applies

Here are scenarios that mirror what I see regularly in practice:

A two-family detached home, two stories → IRC

A three-family dwelling, even if it looks like a suburban house → IBC

A row of townhouses, each three stories with fire separation → IRC

A four-story townhouse, even if identical to the others → IBC

A garage, shed, or studio attached to an IRC home → IRC

A small building with a café on the first floor and apartments above → IBC

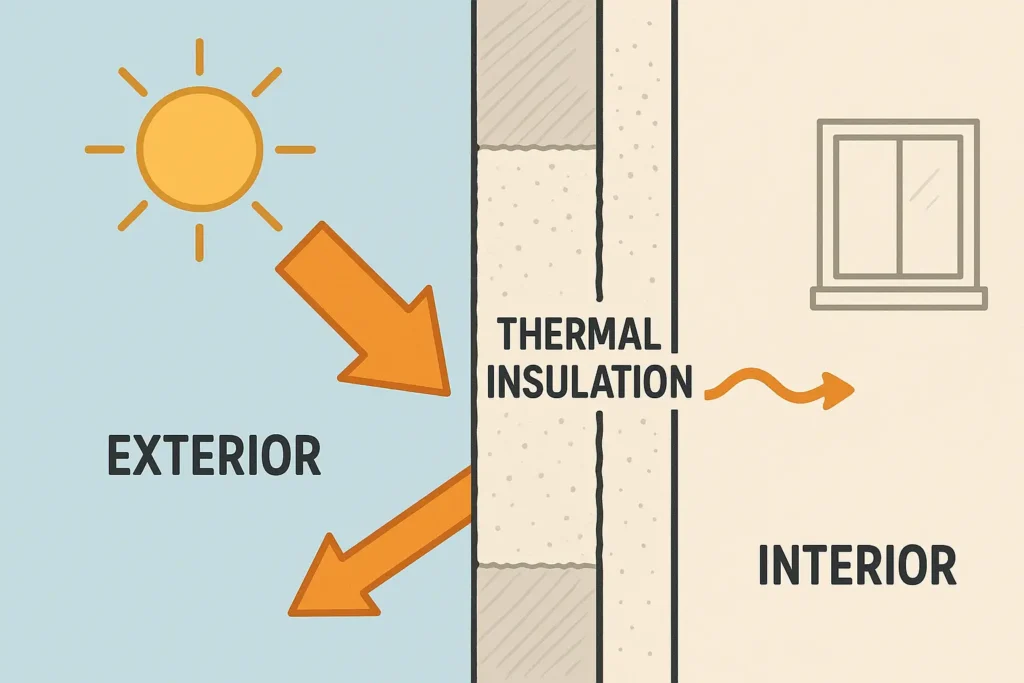

These distinctions matter because they shape everything from wall assemblies to stair specifications to energy performance requirements.

Why Choosing the Right Code Early Saves Time and Money

A project designed under the wrong code can lead to rejected permit submissions — one of the most frustrating setbacks for homeowners and builders. And shifting from IRC to IBC midway usually requires adding engineering, modifying structural systems, or redesigning egress paths.

Understanding the correct code early allows:

accurate budgeting

realistic architectural expectations

smoother plan review

coordinated engineering decisions

fewer surprises during construction

I’ve seen projects stay perfectly on track simply because the team understood from the start whether they were designing to IRC or IBC standards.

Bringing It All Together

Although the IRC and IBC often appear side by side in discussions, they serve very different purposes. The IRC is a streamlined code tailored to typical homes; the IBC is the universal code that governs everything else.

The simplest way to think about it is this:

If your building is a one- or two-family dwelling or a three-story townhouse, the IRC applies.

If it’s anything else, the IBC does.

But behind that simplicity is a world of architectural and regulatory nuance — the kind I see regularly when guiding clients through design decisions, cost considerations, and code compliance.

Understanding the distinction doesn’t just help with theory. It helps with planning, budgeting, and building smarter, safer structures that meet the standards intended to protect the people who live in them.